A few centuries ago, appearing in public with your head uncovered was unheard of. This applied to both men and women.

There were, of course, exceptions, like going to church for a service, for example. But in almost all other cases, the "straight-haired" were treated with condemnation.

In ancient times, many signs were associated with the headdress.

It was believed that losing a hat meant mild madness caused by a strong feeling. Such inattention once predicted falling in love to the point of complete self-forgetfulness.

The people used to say: "If you lose your hat, get ready to lose your head."

And in general, cases where this wardrobe item was lost did not bode well.

It was strictly forbidden to find someone else's hat and use it for its intended purpose. It was believed that this would lead to a migraine or that someone else's thoughts would enter one's head.

If a woman found and tried on a man's hat, it predicted her imminent disappointment in her loved one and the crown of celibacy.

For five centuries, headdresses were treated with special respect. They were not only part of the image or an element of the wardrobe, but also carried a sacred meaning and served as amulets.

But before we talk about them, we want to talk about women's hairstyles. After all, in ancient times, both served as guidelines for determining a woman's status in society.

Girls' and women's hairstyles differed significantly from each other.

During the time of Kievan Rus, girls had the custom of walking with their hair down. This tradition was preserved for many centuries.

And only closer to the 20th century, such a hairstyle was, rather, an exception, and was replaced by braids. Loose hair appears only in wedding ceremonies.

There was also a separate format of hairstyles for holidays and weekdays.

For example, girls from the left-bank Dnieper region braided their hair in one braid on holidays, which fell freely down their back, and on weekdays in two, and placed them around their heads in a wreath.

On the Right Bank, girls braided two braids on weekdays and on holidays. Only on holidays did they fall freely, and on weekdays, like their "neighbors," girls tied them around their heads.

In the Poltava region, girls sometimes braided their hair in a different way. They wove one large braid and several small ones. They wove bright ribbons and laces into them.

They also had more complex hairstyles in their arsenal.

For example, part of the hair in front was separated, a straight parting was made and let down on both sides of the forehead, and the ends of the hair were tucked behind the ears. This is what the hairstyles of that time looked like.

Wreaths served as decoration instead of headdresses for unmarried girls.

However, it was not appropriate for a married woman to braid her hair or walk around with her head uncovered. “Lightening her hair” was a great sin until the beginning of the 20th century.

It was believed that a "straight-haired" married woman brought about crop failure and illness. Therefore, the hairstyle was done in a way that did not interfere with wearing a turban or other headgear and helped to fix them.

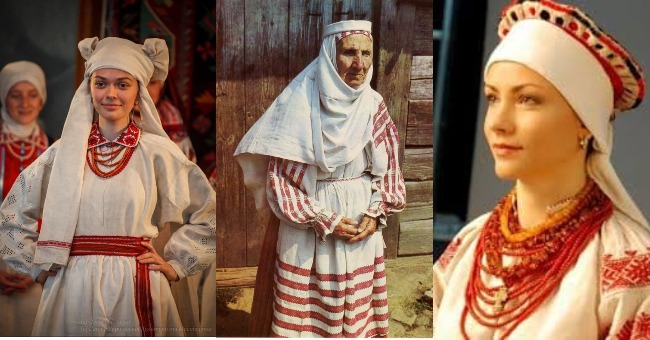

The namitka was an element of Ukrainian traditional clothing for a long time, from the 15th to the end of the 20th century. It reached up to 5 meters in length and was about 50 centimeters wide.

This headdress had many variations of names, depending on the region - nametka, premetka, namytets, serpanok, rantukh, sklenderyachka.

In the 15th century, its most common name was "serpanok." However, it was the serpanok that also existed as a separate wardrobe item.

The difference between a veil and a sari was that a sari was made from ordinary cloth, while a veil was made from thin, almost transparent cloth.

In the 18th century, the industrial production of shawls and veils was established. And already in the 19th century, this women's adornment was known throughout Ukraine. At that time, they began to be woven from the best varieties of flax and at home.

At the beginning of the 20th century, people often inherited greenish or bluish raw silk scarves from their grandmothers, because in those days they no longer knew how to make such things.

A little later, they almost completely fell out of use.

There were up to thirty ways of tying them on the head. The most common was when one end of the thread was passed under the chin, and the other fell on the back.

In western Polesie, the turban was knitted by folding it five times lengthwise and tying it in a bow or knot at the back of the head. There was also a variant with two bows on the sides or above the forehead.

There were also more complicated versions of tying - when both hanging ends and a loop from part of the cloth were left behind.

Sometimes the already knitted pattern was fixed with long pins. This made it possible to put it on and take it off without losing its shape, like a hat. Such pins were made of wax, pieces of fabric or corrugated paper.

In the Hutsul region, the namitka was two-layered and consisted of a lower, white namitka, and an upper, red, floral scarf. It was tied in a semicircle above the forehead, connecting the ends into a knot on the crown. During Lent, people wore only a white namitka, and the red one was not tied.

Many factors influenced how to wear the dress: age, marital status, and life situation. For example, in the Chernihiv region, sometimes elderly women tied it so that one end was passed under the chin. But in the Konotop district, this method was used only in dresses for funeral ceremonies.

There were many ways to dress in a kilt, and even in one village there could be several of them.

The technology of tying is still remembered by elderly women in Polissya and the Carpathians. Today, there are even special master classes where this ancient ritual is taught.

Of course, the markings did not always have the laconic appearance of a simple canvas everywhere and were also decorated , both for fun and to give them a certain meaning so that they could serve as amulets.

In the northwestern regions of Polissya, the namitkas were decorated with ribbons. This type of decoration imitates a girl's headdress and performs the same protective functions.

The ends of the hem were decorated with embroidery of rectangular stripes, and it was often the case that a narrow stripe was embroidered or woven on the forehead.

Taking advantage of the fact that part of the lining was hidden when knitting, Polesie women decorated it with different ornaments on both sides - they embroidered different ends and two different foreheads, and wore it alternately with these sides as desired. The ornaments, by the way, were embroidered so that they looked identical from the outside and the inside. Using the techniques of double-sided cross, quilting, braid and straight stitch.

In Podillia, light linen, cotton, and silk threads were used for embroidery on light-colored threads, emphasizing not the visuality of the color, but the relief of the embroidery.

Red, black, and metallic (gold or silver) threads were used for colored decoration.

Women's jewelry was also decorated with beads.

In modern society, you can tell if a woman is married just by looking at the ring on her finger. However, today not everyone follows the ritual of exchanging rings, so the likelihood of making a mistake when trying to guess is very high.

In ancient times, there were certain attributes for each life cycle of a person. For example, girls decorated their heads with wreaths, braided braids and wore their hair loose decorated with flowers. But married women were not allowed to do any of this. There were certain ethnic norms that were strictly observed.

As soon as girls got married, a new cycle of their lives began in a new role. Indicators of a married woman were her hair gathered and hidden under a headdress.

The first time a girl wore a headdress was at a wedding. The ritual of changing the headdress was called “ochipyn” or “covering”. Its main role was to indicate the new status of the bride. It was put on the bride by her godmother after the wedding. The girl sat on a bread bowl or an upturned sheepskin coat (a symbol of fertility), her maiden attributes, a wreath or ribbons, were removed, her braid was untied, and the mother threw the headdress over the girl twice, but the bride threw it off. Only on the third time did she leave the headdress behind as a sign that she agreed to say goodbye to her maidenhood.

In some regions, the hands of newlyweds were tied with a thread at the wedding. This action was supposed to ensure a strong family.

There was also a custom in which a young man who was being sent off for marriage would sit with his friends near a wedding tree, and his mother would place a loaf of bread in front of him and cover it with a blanket as a sign that he was no longer a bachelor. The day before the wedding, the groom would send messengers to the bride with gifts, including two loafs of bread, a bottle of liquor, a hat, a red scarf, and slippers.

In ancient times, not only the bride was covered, but also a girl who had sexual relations before marriage, became pregnant, and was about to give birth. She was called a "covering." This ritual was performed only by married women.

Not only wedding rituals are associated with this attribute.

The namika was also used in childbirth rituals. For example, the midwife would receive a newborn girl with the same namika that was tied on the girl's head at the wedding - so that she would be a good housewife and have a long life. This namika was kept for life.

In the Hutsul region, to ensure the protection of the mother and child, when saying goodbye to the midwife on the first day after childbirth, they gave her a shawl, scarf, or embroidered mittens.

In the Carpathians and Volyn, this traditional women's adornment survived until the second half of the 20th century. Now it is a real rarity and such scarves can only be found in museums or families where they have remained as an inheritance.

Write a comment