What does this slogan mean? Who coined it, when did it come up with it, and what was it used for?

We find answers to all these questions below.

Ukrainian unions stopped Canadian emigration

The slogan “each to his own in his own way” gained considerable popularity in the late 19th century in Galicia. According to the well-known Ukrainian historian, local historian, teacher, and researcher at the Center for Research on the Liberation Movement, Igor Fedyk, it was this motto that marked the heyday of cooperative entrepreneurship in Western Ukraine.

Until then, the entire commercial business of that time was in the hands of the Polish nobility and wealthy Jews. Ukrainian peasants suffered greatly from this situation in economic terms. Therefore, boycott sentiments spread throughout the region and, of course, found their reflection in the creation of cooperatives. Such business became not only an economic salvation, but also served as a step towards national unity. The basis for the flourishing of Ukrainian business in Galicia was the slogan “each to his own, in his own way”. This principle changed the course of popular consciousness and helped the economy “get up”. (Newspaper “Lvivska ratusha”).

It is impossible to ignore the fact that the first wave of Canadian immigration occurred precisely at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Due to high financial instability and inability to achieve economic development, many people went abroad to work. Therefore, the active creation of cooperatives significantly stopped this process. The slogan “each to his own” by its very name makes it clear that the newly created entrepreneurs called on Ukrainians to buy goods and services only from each other for the sake of economic development.

The idea of creating “granaries” – large storerooms where all the local people would take the remains of their own grain – seems interesting. Everyone would give as much as they could and considered necessary. From these reserves, grain was distributed to the needy during the winter, and before the sowing campaign, it was sold, and each of the “contributors” would receive their percentage of the sale, depending on the amount of grain brought.

Peasants actively united in cooperatives and independently set market prices for their goods.

“Our beans were taken all the way to Brazil,” says Stepan Heley, a 72-year-old professor and head of the Department of History and Political Science at the Lviv Commercial Academy. “The average Ukrainian peasant 100 years ago was not much different from today. A man has two hectares of land. How can he live on them? And what of those two hectares if an American farmer has 200 or 300. The only way out is cooperation. 15–20 farmers unite. They create, say, a vegetable growing cooperative. They elect the most intelligent one as the head. They save up money, buy the most necessary equipment. Then, when the first profits appear, they buy more. They create several stores: one in Lviv, the second in Kalush, the third somewhere else. They start working.

What can our peasant sell abroad now? Nothing. Previously, Ukrainian beans were transported all the way to Brazil. They met all the standards. Or eggs. No one sold as many eggs as Ukraine sold to the world. But for this, it was necessary to bring roosters of special breeds from other countries. These roosters were kept in a cage and were only allowed to approach their own hens. They had a special mold - an egg fits in it, so it can be transported. Have you heard that some winter someone gathered people in the village and said: let's change potato varieties? Take this one, disinfect the land, don't give this or that fertilizer, don't give that or that. And then there were a lot of different courses in the winter. All this raised the level of management.

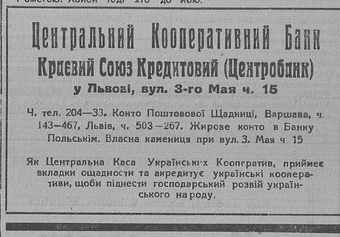

Small cooperatives in each industry were united into unions and associations. Trade unions, dairy cooperatives, credit unions, etc. emerged. It was so mutually beneficial and exciting that within a few years of active development of cooperative entrepreneurship, Jewish and Polish capital was practically pushed out of Galicia.

For comparison, in 1921 there were 580 Ukrainian cooperatives in Western Ukraine, and in 1939 there were about 4,000.

“Ukrainian money – in Ukrainian hands – for Ukrainian affairs!”, or How Europeans bought eggs

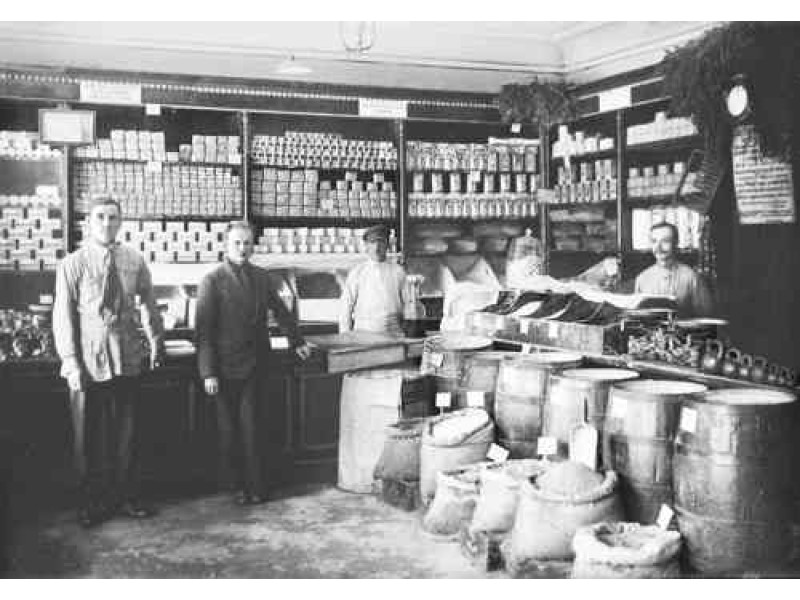

The very first cooperative store was founded back in 1883 by architect Vasyl Nahirny and priest Yevhen Dudkevych. They named it "People's Trade."

A little later, it grew into a large network of wholesale warehouses and shops. For example, in 1904, 831 small Ukrainian shops cooperated with "Narodnaya torgovlya". This cooperative also established wholesale supplies "from the manufacturer" and taught Ukrainians how to conduct trade.

Between the two wars, "Narodna torgovlya" organized the sale of "colonial goods," that is, imported grocery products. Thus, in 1934 alone, the cooperative sold four carloads of coffee, one and a half carloads of pepper, three carloads of prunes, a carload of nuts, and half a carload of cumin.

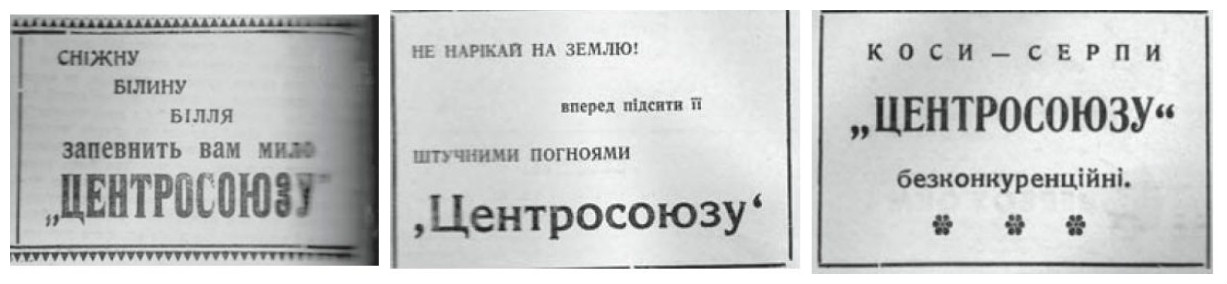

Instead, the trade union “Tsentrosoyuz”, organized by Teofil Kormoś, a lawyer from Przemyśl, exported Ukrainian peasant products to Western Europe. For example, in 1935, the union signed a contract with Spain. From March to November of that year, Ukrainians exported 700 wagons of eggs, and for the rest of the season, 1,600 wagons of oranges were sent from Spain.

“They say that since “Centrosoyuz” started selling oranges, the village of Yaykivtsi in Zhydachiv district changed its name to Pomaranchivtsi,” the humorous magazine “Komar” jokingly wrote.

Kosov craftsmen from the Carpathian region united in the cooperative "Hutsulshchyna". They sold carpets, bedspreads, and embroidered dresses.

“This cooperative was founded by our Hutsul artists, who have extensive experience in the production of weaving, carpet-making and carving handicrafts. Therefore, all the products of this cooperative are made of the best material, solidly finished, patterned on stylish, Ukrainian patterns of our best artists. This cooperative takes full responsibility for all its products, as well as for the quality of the material,” the press of the time assured.

It even got to the point that Poles and Jews would sew the "Hutsulshchyna" trademark on their manufactured goods.

In the press of Galicia during the interwar period, the word "lonely" often appears in advertising texts alongside the word "Ukrainian" in the meaning of "unique."

For example, in an advertisement from an insurance company: “Take out life insurance immediately in the only Ukrainian mutual insurance company for life “Karpatiya”. Or: “We do not buy other products, only from the only Ukrainian cooperative factory “Produktsiya”. Marmalades, juices and jams of “Produktsiya” can be found in all Ukrainian consumer stores.”

Or something like this: “Demand for genuine Ukrainian shoe pegs everywhere, only with this sign of the lone Ukrainian factory “Dendra” in Lviv!” And next to it a warning: “Be careful, because the Jewish cartel is hiding under our packaging!”.

As we can see, Ukrainian cooperatives were truly "lonely," so they had to win back every client, as they were. So the principle of "each to his own" that was raised during the First World War fell into fertile ground.

Every conscious Ukrainian should use only domestic products and ignore all other manufacturers. Another slogan of the time was the phrase “Ukrainian money – in Ukrainian hands – for Ukrainian affairs!”.

“Our native industry and trade are growing before our eyes,” wrote a newspaper called “Svyy do svyy” in 1935. “They are developing not only thanks to the initiative and resourcefulness of individuals, but also thanks to the growth of Ukrainian nationalism. The cry “Svyy do svyy” is resounding louder and louder, embracing wider and wider circles. There are already entire phalanxes of people who persistently seek Ukrainian products everywhere, which they buy only in their stores, even when it is associated with disadvantages for them.”

Ukrainian-made goods were of high quality, so they quickly entered the European market. This state of affairs made cooperatives a very profitable business for the local peasantry. Galician dairy products, which were exported to Germany and France, deserve special attention, because the demand for them was very high even there.

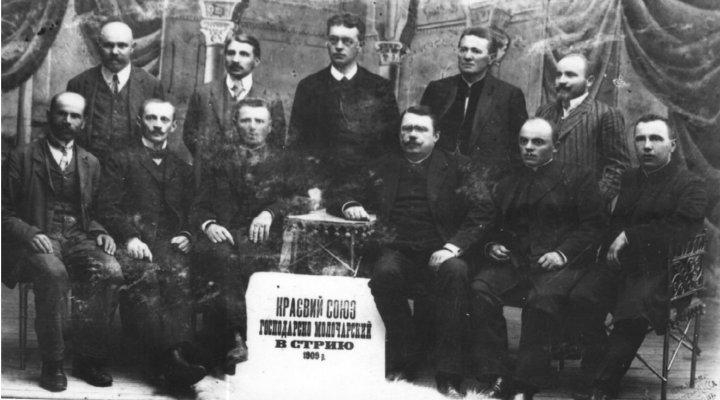

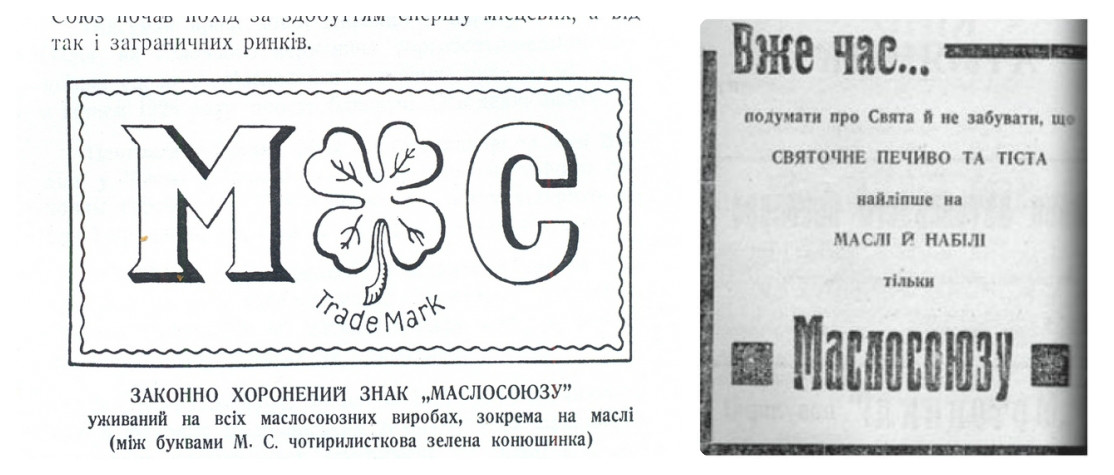

"Maslosoyuz" was the pride of Ukrainian industry. The union of milkmen of various cooperatives was founded by the priest and composer Ostap Nyzhankivsky from Stryi back in 1904. The emblem of the union was the letters "M.S." and a clover leaf between them. Such a mark was considered a true sign of quality. Even the Polish nobility noted that "butter with clover" was the best.

More than 200,000 small farms from Volyn and Galicia delivered milk to the milk collection center of the Maslosoyuz. From there, it was sent to district dairies, of which there were more than 1,500. There, the collected milk was processed into butter and other dairy products and transported throughout Galicia and abroad.

In 1935, 423 tons of butter were exported. They laughed that Ukrainians would conquer the world thanks to their cows. The self-published publication "Maslosoyuznyk" published a fictional humorous speech by one of the company's founders: "Dear community! It's not far off when district residents will scatter all over the country, and every house will have its own creamery... And some will have two. We will no longer transport milk in thirty- and fifty-pound trucks, but will order tankers. We will build mountains out of butter and cover England, America, Africa, Antarctica with it... And the rolls of Ukrainian hams and sausages will flow for butter and spread the glory of Ukraine everywhere... And the Zulus, and the Hindu, and the inhabitant of Tierra del Fuego or the Bushman - everyone will remember us, consuming our exhibits, and will take an example from us. Because we are destined to be the creators of the butter era of the Universe!"

Advertising is the engine of cooperative progress

Jokes aside, it was thanks to advertising that Ukrainian goods were known abroad, says Mr. Fedyk. "By 1939, almost a hundred newspapers were published in Galicia. And each of them had advertisements about our cooperation. Foreign businessmen read the newspapers, who "went out" to buy Galician products."

In 1935, the "Guide to Ukrainian Firms and Institutions in the Region and Abroad" was published in Lviv, and at that time it had almost 200 pages (!).

Looking at that catalog, one can easily assume that the Galicians of that time could easily live, using only the goods of their compatriots. Having feasted on Ukrainian meat from "Tsentrosoyuz", having drunk Ukrainian milk from "Maslosoyuz", having tasted Ukrainian sweets from "Fortuna Novaya" with "Prazhin" coffee or its substitute "Luna" from the cooperative "Suspilny Promysl". Later, having polished their shoes with "Elegant" cream, of course, Ukrainian, they would go to a tavern in the also Ukrainian "Narodnaya Gostinnytsia". And there, smoking "lonely" domestic "Kalina" cigarettes, they would read the magazine of the concern "Ukrainian Press".

In addition, the directory provides addresses and phone numbers of dozens of Ukrainian lawyers, butchers, locksmiths, carpenters, and even violinists and pianists.

“Ukrainians! Buy goods only from companies that advertise in the Ukrainian press,” the Lviv daily newspaper “Dilo” urged in early 1934. In another issue, it also declared: “How can you, an intelligent person, do without “Dilo” in these times? If it is too difficult for you to pay for our magazine yourself, then subscribe to “Dilo” in partnership with your neighbor.”

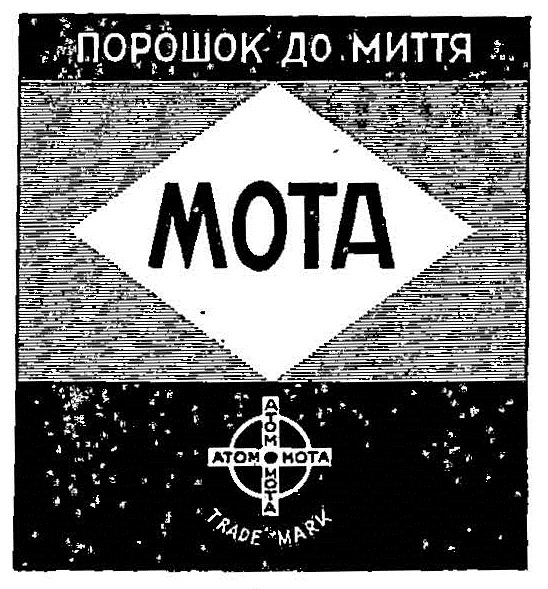

The advertising texts of that time seemed to leave consumers no choice: “Ukrainian housewives! Demand and use only Ukrainian-made “Mota” washing powders and detergents,” “You won’t get far in shoes that aren’t cleaned with “Elegant” toothpaste,” “Desire only “Kalina” papers – they are the best and yours.” Or another option: “As much honey as bees have – so much “Kalina” to the smoker.” Polish cigarettes were often better than “Kalina,” but if you smoked a gentry “brand” in Ukrainian society, it could even lead to a quarrel and a fight.

The Przemysl confectionery factory “Fortuna Nova” distributed “commandments of a conscious Ukrainian.” Among them were the following: “You will not use other candies and sweets, only the one Ukrainian factory “Fortuna Nova”, “Never go to a young lady without candies from “Fortuna Nova”, if you do not want to lose her”, “Do not treat anyone with other people’s sweets, because they very often contain all sorts of filth – thus do not undermine anyone’s health”, “That every Ukrainian, regardless of his party affiliation, must belong to one all-Ukrainian party of Admirers of “Fortuna Nova” products”.

In the late 1930s, the factory employed 125 people. They produced about 5 tons of sweets every day. They had shops in Lviv, Drohobych, and Stryi.

The series of chocolates “Sweet History of Ukraine” was especially popular, with portraits of rulers on the wrappers, from Volodymyr the Great to Pavel Skoropadsky. “Sweeter than honey, tastier than sleep – sweets from “Fortuna Nova”,” the advertisement assured consumers. By the way, “Fortuna Nova” survived the war, the Soviet era and became the modern and familiar “Svitoch”.

About support and obstacles

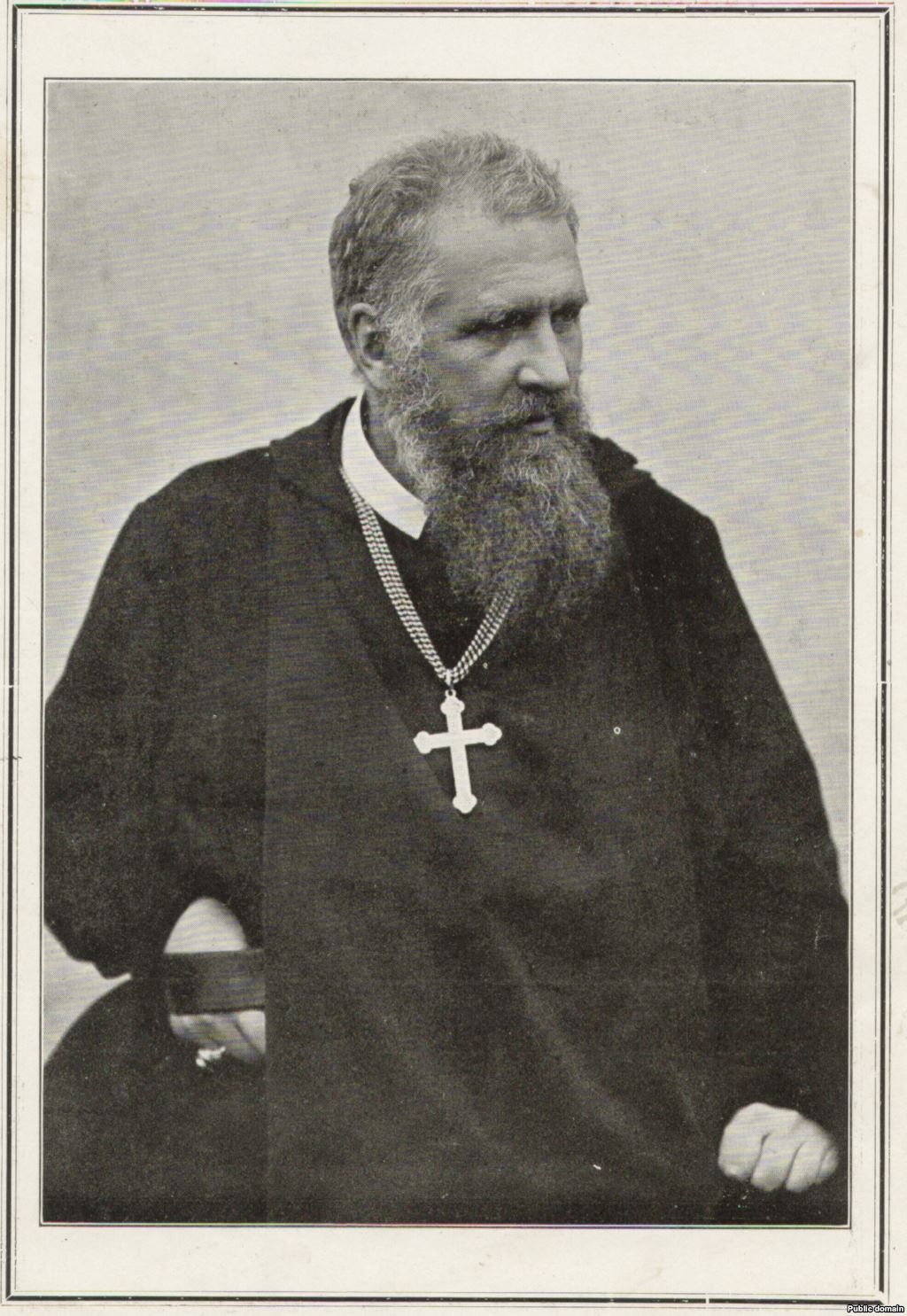

The Greek Catholic Church played a leading role in the formation of the cooperative.

At the request of Metropolitan Andriy Sheptytsky, the process of creating cooperatives was supported by the church and led by Father Tyto Voynarovsky. The Metropolitan himself published an entire work “On the Social Quest” in 1904. In this work, Mr. Sheptytsky justified the grounds for creating cooperatives and instructed priests to organize entrepreneurs “on the ground.” In addition, it was the Metropolitan who organized special schools where future cooperators studied.

“There were several educational institutions in Lviv where Ukrainian youth were taught about cooperatives,” continues Ihor Fedyk. “The children of the peasants had the opportunity not only to get a good education, but after graduation they were sent to work in rural cooperatives. By the way, there were a lot of girls among the students. It is worth noting that in this way the Metropolitan formed the future rural intelligentsia. After all, usually in the villages, apart from the priest, there was no one from the intelligentsia. Even the teachers were often Poles.”

Of course, there were many obstacles on the path to creating economic independence. The organization of cooperatives was carried out in a constant struggle for existence.

“It was extremely difficult to develop cooperation,” says Mr. Fedyk. “The Polish authorities, persecuting nationally conscious patriots, also persecuted Ukrainian cooperation. After all, they understood that such an initiative would displace Polish business, and in addition, the police guessed where part of the earned money went.

For example, in 1930, when the so-called "pacification" took place, many cooperatives were burned and destroyed along with the buildings of "Prosvita".

Ukrainian cooperation in the 1920s and 1930s is a unique phenomenon in European history. I am not sure if any other nation without a state was able to put this direction on its feet like this,” says Stepan Heley. “Although there were enough obstacles.”

The Polish state did not want Ukrainians to develop their economy. Because where there were wealthy owners, there appeared "Prosvita", "Sokil" and other patriotic organizations. And who knows - suddenly they will start financing the underground OUN. That's why they imposed a lot of restrictions.

For example, as soon as Maslosoyuz started to get on its feet, Poland put forward new requirements for dairy products. Commissions inspected farms – what the cow ate and from which side the light shone on it. Even the material from which the dishes should be made was stipulated. They thought this would ruin Ukrainian dairy farmers. But it turned out the opposite – they fulfilled all these requirements and produced the best butter in the country. Modern Poles remember the stories of their grandfathers – how they secretly bought butter from Maslosoyuz. So that none of their Polish neighbors would find out.

On the other hand, it was beneficial for the state to support the cooperative movement. After all, this was revenue for the budget. Polish cooperators were given loans at symbolic interest rates. But their cooperatives in Galicia were weak - there were few Poles living here, and there were almost none in the villages. Ukrainians were also offered loans, albeit on less favorable terms. They mostly refused. Because they knew: today they give money, tomorrow they will start dictating the terms. Why were Ukrainian cooperatives a level higher than Polish and Jewish ones in interwar Galicia? The elite of the nation worked there. It was impossible for a Ukrainian intellectual to get a government job in Eastern Galicia. Then Krakow - please, and on their own land - no. That's why they went to cooperatives. Most cooperators studied abroad. That is, they had experience of European life. The most successful, such as Kostya Levytskyi, earned fortunes. It is to him that the words belong: "Strangers come and go, but the master remains in the house."

But no matter how difficult it was to create a cooperative in Galicia, starting it in other territories of the country was a total effort.

“One of the first to decide to create cooperatives in the rest of Ukraine was Levytsky,” continues Ihor Fedyk. “The son of a priest who studied in Kyiv, saw the economic effect of cooperation in Galicia and, as a result, national uplift. When he returned to Tavria, he founded the “Workers’ and Farmers’ Union.” On the other side of the border in Ukraine, capital was usually concentrated in the hands of Russians and Jews. Although there were also a few rich Ukrainians. As they would now call them, oligarchs. Levytsky published his first brochure about cooperatives in Lviv and secretly smuggled it to Greater Ukraine, where it was semi-secretly distributed among Ukrainian peasants.”

"Of course, cooperatives played a unifying role, because at that time many Ukrainian peasants did not have a strong national consciousness. Instead, the "To each his own" movement reminded peasants of their own identity," the historian continues.

The stronger Ukrainian cooperatives became, the more money they allocated for national causes: book publishing, funding orphanages, scholarships for poor students... Of course, cooperatives provided money for underground political national organizations.

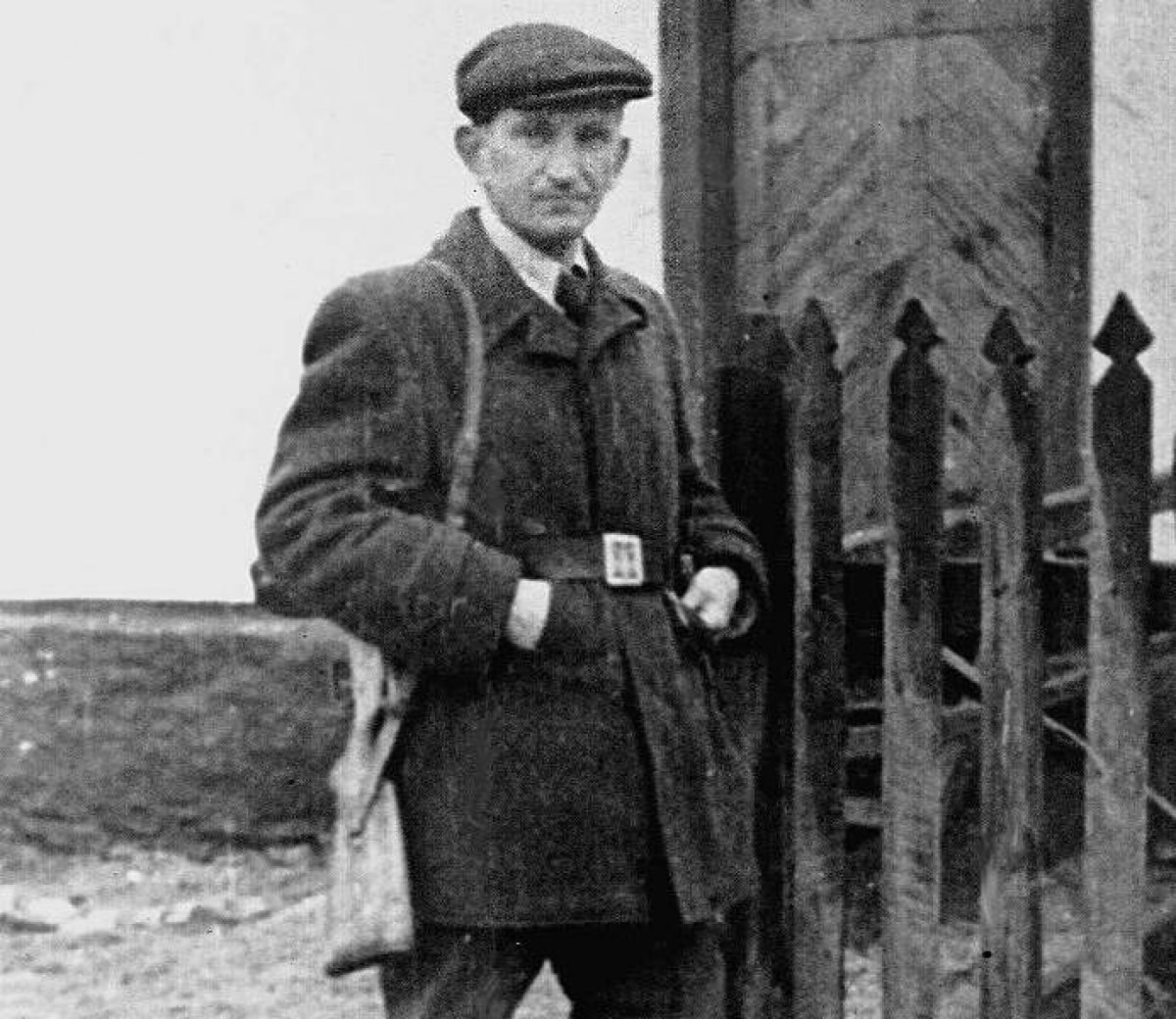

By the way, Ukrainian cooperation allowed Roman Shukhevych to establish and run a successful advertising business. Already in 1937, the “politically unreliable” Shukhevych, after serving a sentence for participation in the OUN, could not find a good job, despite two higher educations. Therefore, he founded the first advertising company in Galicia, “Fama”. It was thanks to the principle “To each his own, to his own” that Roman Shukhevych’s advertising business had a considerable clientele.

The slogan “To each his own” persisted in Galicia until September 1939, when the region was occupied by Soviet troops. All enterprises were nationalized – Polish, Jewish, and Ukrainian. And most of their owners were exiled far from their native places.

Now this idea is gradually being revived, mainly in the minds of Ukrainians. The events of recent years force us not to forget our own history, "not to shy away from our own" and to support each other in every way.

So, come to your own place and get your own and all sorts of good things for us. =)

Write a comment