A hundred years ago, the terrible events of the rebellious year of 1918 added a tragic and at the same time heroic page to the history of Ukraine - the battle of Kruty.

Historical background

On November 7, 1917, the Central Rada, headed by Mykhailo Hrushevsky, fulfilling the will of the Ukrainian people, proclaimed the Third Universal of the Ukrainian People's Republic and set out to build an independent state.

In the photo: the UNR board.

However, Russia clearly had no intention of giving up a piece of the pie in the form of Ukraine, granting it autonomy. Such actions of the Ukrainian political elite led to a significant aggravation of relations between the countries. And on December 5, 1917, the Bolshevik Russian government of Lenin-Trotsky declared war on the UNR.

On December 12, 1917, the All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets in Kharkiv proclaimed Ukraine a Soviet republic. At the end of December 1917, Soviet power was established in the Kharkiv, Ekaterinoslav, and Poltava provinces. Under these conditions, in order to accelerate the conclusion of a peace treaty with the Quadruple Alliance, on January 9, 1918, the Ukrainian people declared Ukraine an independent state by the IV Universal. These actions led to a military offensive on the territory of our country.

Meanwhile, from almost 300,000 troops loyal to the Central Rada in the summer of 1917, in January 1918 the number of troops loyal to the UNR had decreased to about 15,000 people throughout the country due to the demoralized state of the army as a whole, war fatigue and the incredibly powerful propaganda of the Bolshevik revolutionary agitators, who in turn swayed entire units of the Ukrainian army to their side. Another destructive factor for the UNR was the number of supporters of Bolshevism in Kyiv and the country as a whole. And one of the decisive factors was the uprising of the workers of the Arsenal factory, which, although suppressed, posed a real threat to the UNR system. The operation to capture Kyiv by the Bolsheviks was commanded by Mykhailo Muravyov, whose unit numbered up to 6,000 people, armed with machine guns and artillery.

Red offensive

Unfortunately, the Ukrainian command failed to properly assess the strategic situation. While the Bolsheviks were preparing for an offensive in the Bakhmatsk direction, the headquarters of the Kyiv Military District expected the main blow from the direction of Poltava.

At a rally in Bakhmach, Muravyov called on his soldiers: "Our combat mission is to take Kyiv... There's no point in pitying the Kyiv residents, they tolerated the haidamaks - let them know us and accept the payment. Without any pity for them! They will pay us with blood. If necessary, we will leave no stone unturned."

Due to leadership errors, the most combat-ready units were sent to the Poltava direction: the 1st Hundred of Sich Riflemen, the Black Haidamaks Combat Battalion of the 2nd Ukrainian Military School, and the Serdyutsky Detachment of the P. Doroshenko Regiment (a total of 500 fighters).

But 300 exhausted young men from the 1st Ukrainian Military School ended up being sent to Kruty.

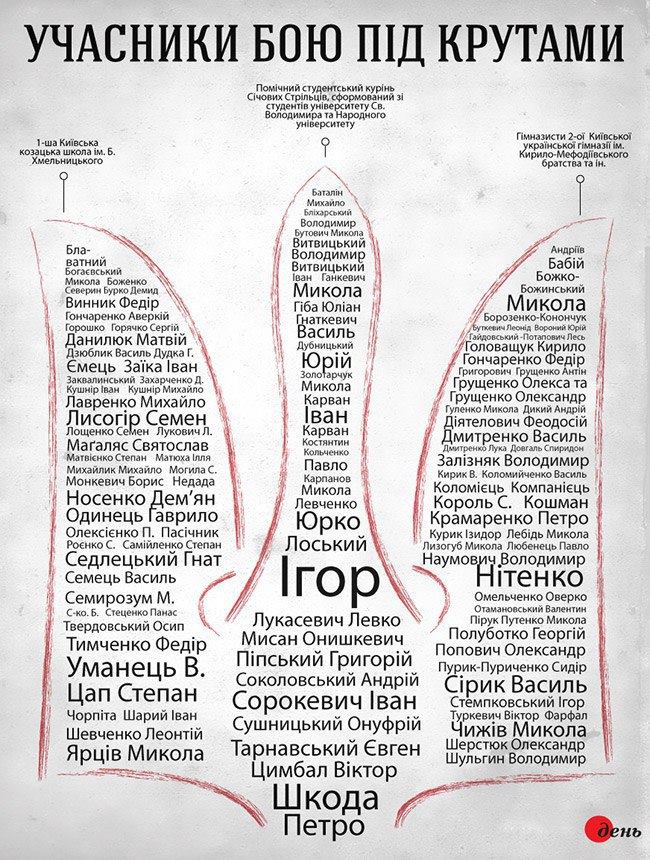

Designed to provide security services in Kyiv, the Auxiliary Kurin was created in mid-January 1918 on the initiative of patriotic Ukrainian youth – students of St. Volodymyr’s Kyiv University and the Ukrainian People’s University, as well as students of the 2nd Ukrainian Gymnasium named after Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood.

The kuren consisted of one hundred, numbering 120 people - students, gymnasium students, and students of the paramedic school. The kuren's ataman was a student S. Korol, and the 1st hundred was commanded by a student of the Ukrainian National University, T. Omelchenko.

Participant of the battle near Kruty, Igor Losky, a student of the Kyiv Cyril and Methodius Gymnasium in 1918, recalled: "The then Ukrainian government hopelessly missed the moment of national upsurge that swept the masses of the Ukrainian army, when it was possible to create a real Ukrainian army... And only at the moment when the catastrophe was already inevitable, some of the Ukrainian statesmen came to their senses and began to hastily create new units, but it was already too late."

So, literally three weeks before the battle, the Student Kurin of the Sich Riflemen was created. The unit was considered voluntary, but in fact, enrollment was voluntary and forced. According to Lossky, the decision to create the kurin was made by the student council of the University of St. Volodymyr and the newly formed Ukrainian People's University. There were not very many people who wanted to join the kurin, so the meeting decided that "deserters" would be boycotted. Only a little more than a hundred people signed up for the student kurin.

The military warehouses were full of equipment and ammunition, but the kurin received torn overcoats, soldier's trousers and prisoner's caps. "You can imagine, writes Lossky, how grotesque the hundred looked. A private looked like this: his own boots, soldier's trousers tied with a rope, a student jacket or civilian vest and on top an overcoat, which was missing at least one hem ... old rusty rifles."

Most of the soldiers hardly knew how to handle weapons. However, despite the lack of proper military training, students and gymnasium students, full of patriotic feelings, did not hesitate to go to save their homeland. As another memoirist recalled, "one only had to look at their faces and see the exalted expression in their eyes to understand that all reasonable arguments were powerless to change their decision to go to the front and fight with the enemies of the Ukrainian state."

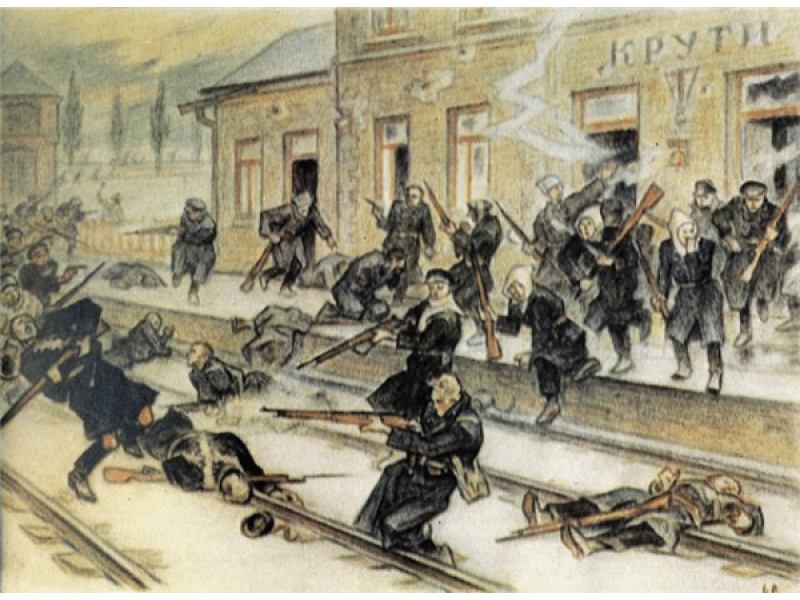

Battle of Kruty

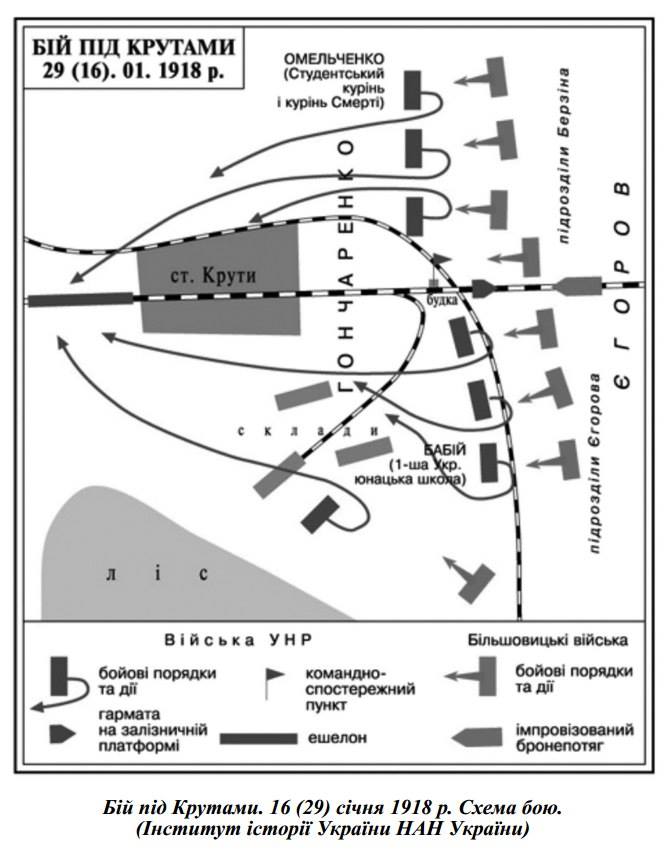

Immediately after arriving in Kruty, Captain A. Goncharenko sent the young soldiers (away from the railway, to the extreme left section of the positions. "The student company was given one or two clips with a warning to behave carefully, as there were many who did not know how to shoot," recalled one of the Sich soldiers.

In the photo: Captain Goncharenko Averkiy Matveyevich, still in the rank of second lieutenant in the Russian Imperial Army.

To make it more difficult for the Reds to advance westward, the railway connecting the Plysky and Kruty stations was damaged. On the evening of January 29, an attempt was made to damage the railway tracks in the direction of Bakhmach. But the Red Guards repelled the attack, not allowing themselves to be cut off from this connection.

Having despaired of the possibility of resisting the Reds, the 13th Sich regiment went underground for demobilization. Under the command of Captain D. Nosenko, 100 free Cossacks and soldiers of the Death kuren, 300 young men of the 1st Ukrainian Military School and 116 Sich soldiers of the auxiliary kuren remained.

As A. Goncharenko stated in his memoirs, the total forces of the defenders of Kruty consisted of 20 foremen and 500 soldiers. Nosenko was sure that he would not be able to hold the position without reinforcements. Captain F. Tymchenko went to Nizhyn to try to convince the T. Shevchenko kuren located there to join the defense of Kruty.

The Shevchenko kurin numbered 800 soldiers, but was hostile to the Central Rada. Thus, on January 30, the general meeting of the Nizhyn garrison decided not to offer any resistance to the Red Guards and "to receive the revolutionary detachment with due respect and welcome it as fighters for the working people and provide it with all kinds of support."

Thus, the Nizhyn Kuryn openly declared its support for the Bolshevik government and actually became a traitor in the rear of the UNR.

At this time, it became known that reinforcements from Kyiv had been sent to the Bakhmat sector of the front – Petliura's kuren (300 people). However, the haidamaks had not yet managed to leave Kyiv when they received news of the Bolshevik uprising in the capital.

Not having detailed information about the situation, S. Petliura stopped his train at Bobryk station, in order to return the haidamaks to Kyiv if necessary. Meanwhile, events took place near Kruty, which determined the fate of the entire left-bank front.

In a telegram to the headquarters, Muravyov noted:

"The path to Kyiv seems to be open, but the enemy, retreating, is blowing up bridges and roads, which creates great difficulties for us. At the moment, I am standing in front of Kruty, which I did not take only for the above reasons. The enemy, retreating closer to Kyiv, is beginning to put up fierce resistance."

In total, about 1,000 Red Guards and 2 tank trains were to advance on Kruty station. If necessary, these forces could be tripled by the less combat-ready "revolutionary" units concentrated in Bakhmach.

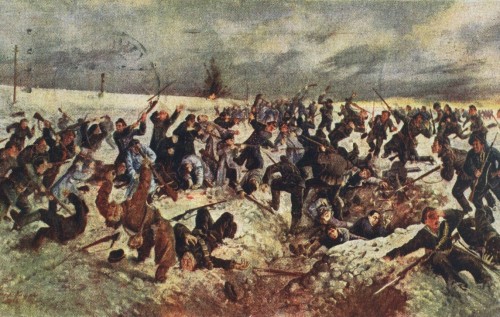

On January 30, it became clear that a Bolshevik offensive was inevitable. Before the offensive, the Ukrainians dug in their trenches on both sides of the railway embankment.

The reconnaissance sent to the east observed the appearance of Red Guard trains on the horizon. Not far from the line of defense, the Bolsheviks slowed down; armed soldiers were hastily unloaded from the cars. As one of the Red Guards recalled, "the fighters of our units were mostly completely ignorant of military affairs, they could not even line up without a jostling."

The Reds confidently went on the offensive first, not immediately noticing the improvised line of defense ahead. A. Goncharenko recalled:

"In the morning the Reds began their offensive in closed columns; it looked as if they were going on parade... The front units of the Reds, marching in closed columns, were obviously confident in our escape. As soon as the Reds approached within a shot's distance, we greeted them with heavy fire from 4 hundred and 16 machine guns. Under direct fire they suffered heavy losses in their ranks. The following detachments were already taking battle formation from the train."

Finding themselves under machine gun fire, the Red Guards quickly realized the complexity of their situation.

"Field, arable land, dirt, it's hard to go, there are no trenches, but there were trenches on the enemy's side and, in addition, the enemy had a large number of machine guns," recalled one of the participants in the attack. "We are conducting a scattered attack from the field, the command is given "Fire!", shooting opens. The front is wide, it is difficult to maintain communication with the flanks ... We pushed forward, the enemy fired back with machine guns, we had wounded and killed. The Red Cross was right there, but the bandages had to be done sometime, we had to go forward." "On the approaches to the station, each of us clearly heard the groans of our comrades who were falling from the enemy's fire," recalled another Red Guard.

When S. Loschenko's train was forced to leave under enemy fire, it became impossible to maintain constant communication between the two defense sectors: the railway embankment was too high. Captain A. Goncharenko immediately brought the reserve 1st Youth Company into position, but the ammunition for the machine guns had already noticeably decreased.

The only thing that saved the Sichkovs was that the pace of the Reds' offensive had slowed down slightly. After suffering significant losses, the Red Guards lay down a few hundred meters from our positions, not daring to attack.

And at the same time, the UNR received alarming news from the rear: the T. Shevchenko kurin in Nizhyn finally declared its support for the Soviet government. This threatened the defenders of the station. Kruty with a blow to the rear. And the Bolshevik commanders finally managed to raise their fighters to the attack and hand-to-hand knock out the gymnasium students from the station. Without delay, A. Goncharenko ordered all units to retreat. The retreat began in the evening darkness, when the enemy on the right wing again went on the offensive.

On many sections of the front, the retreat was disorderly and chaotic. Only the onset of darkness allowed the young men to break away from the enemy.

As A. Goncharenko stated in his memoirs, the total losses of the defenders of Kruty village were 10 foremen and about 250 soldiers – mostly wounded young men of the 1st Ukrainian Military School. In addition, a couple from the student company, among whose fighters was A. Goncharenko’s younger brother, disappeared without a trace.

The Red Guards were approaching and the echelon that was standing was forced to move out without waiting for the rest of its fighters.

Tragic shooting of students

The fate of the missing students of the platoon, who did not have time to join their unit, was tragic. Lost in the darkness, the Sichkovs reached the railway station at a time when it had already been occupied by the Moscow Red Guards and they were all taken prisoner.

The commissar of the 1st Moscow Red Guard detachment, E. Lapidus, said that the only officer among the prisoners was shot by the Muscovites immediately. It was barely possible to persuade the Red Guards not to rush into the massacre of the other prisoners who were being held in custody in one of the Red military echelons.

January 31 was a fatal day for the prisoners. "The next day, when we were traveling to Kruty station, the train stopped on the way by order of Yegorov, all the detainees were taken out of the car and shot with explosive bullets 300 steps from the train," E. Lapidus testified.

Before his execution, a student of the 2nd Ukrainian Gymnasium, 19-year-old native of Galicia, Hryhoriy Pipsky, sang the anthem "Ukraine is Not Dead Yet," and other prisoners joined in.

The results of excavations carried out in March at the execution site showed that a total of 28 prisoners were executed. Despite his own losses, Muravyov was satisfied with the outcome of the battle and believed that he had defeated Petliura himself (who was actually absent at Kruty). On January 30, he sent a message to the People's Commissar of the Soviets and V. Antonov-Ovsienko that "after a two-day battle, Yegorov's First Revolutionary Army, supported by Berzin's Second Army, defeated the Soviet counter-revolutionary troops near Kruty..." Muravyov had no doubt that the fate of the Ukrainian capital had already been decided.

In March 1918, after the Bolsheviks signed the Brest Peace Treaty and the UNR government returned to Kyiv, by decision of the Central Rada of March 19, 1918, it was decided to solemnly rebury the fallen students at Askold's Grave in Kyiv. After that, the feat of the youth near Kruty was forgotten for more than 70 years.

Summing up

The Battle of Kruty will forever go down in history as a symbol of sacrifice and idealism. And at the same time, it exposed all the troubles of inept strategic planning.

If fresh units had gone out to meet Muravyov's main forces concentrated in Bakhmach, and not young men from the 1st Ukrainian Military School and inexperienced youth, the course and outcome of the battle could have been completely different.

In the historical literature of the Soviet period, they tried in every way to keep the battle of Kruty quiet, mentioning only that in January 1918, near the village of Kruty, "fierce battles were taking place between Soviet units and the troops of the Ukrainian bourgeois-nationalist counterrevolution."

The great confusion in the history of the Kruty events is also connected with the date of the battle itself. When in March 1918 the UNR government decided to honor the memory of those killed at Kruty, it turned out that the headquarters of the Ukrainian command did not have detailed information about the time, place and duration of the battle. Most of the documents of the Ukrainian units during these battles were simply destroyed. Determining the date of the battle from the words of the participants also turned out to be difficult, since for many of them it was just an episode of endless fighting.

But the Soviet press indicated the exact date of the occupation of the Kruty station by the "winners" - January 29. In fact, this was an erroneous message from Muravyov's headquarters, which actually concerned the Plyska station. But since there was no other reliable evidence at the disposal of representatives of the Ukrainian authorities, they decided to consider this date as correct.

In the following decades, it was January 29 that became "Kruty Day" for Ukraine. Unfortunately, historians have never tried to explain why in the memoirs of some participants in the battle, including those written immediately after those events, the day of the Kruty feat is still called January 30... Only new archival finds have allowed us to identify inaccuracies and reconstruct in detail the course of the battle near Kruty and the armed struggle in Ukraine at the beginning of 1918.

In Ukraine, commemorations of the Battle of Kruty began only on the eve of the declaration of its independence. On January 29, 1991, a birch cross was erected in Kruty and the first small public rally was held.

At the state level, Ukraine began to honor the memory of the heroes of Kruty only in 2004. A year before that, in January 2003, Leonid Kuchma signed the decree "On Honoring the Memory of the Heroes of Kruty". And only in 2006 was a monument erected at the site of the battle, and on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the battle, the Mint issued a commemorative coin with a face value of 2 hryvnias.

Write a comment